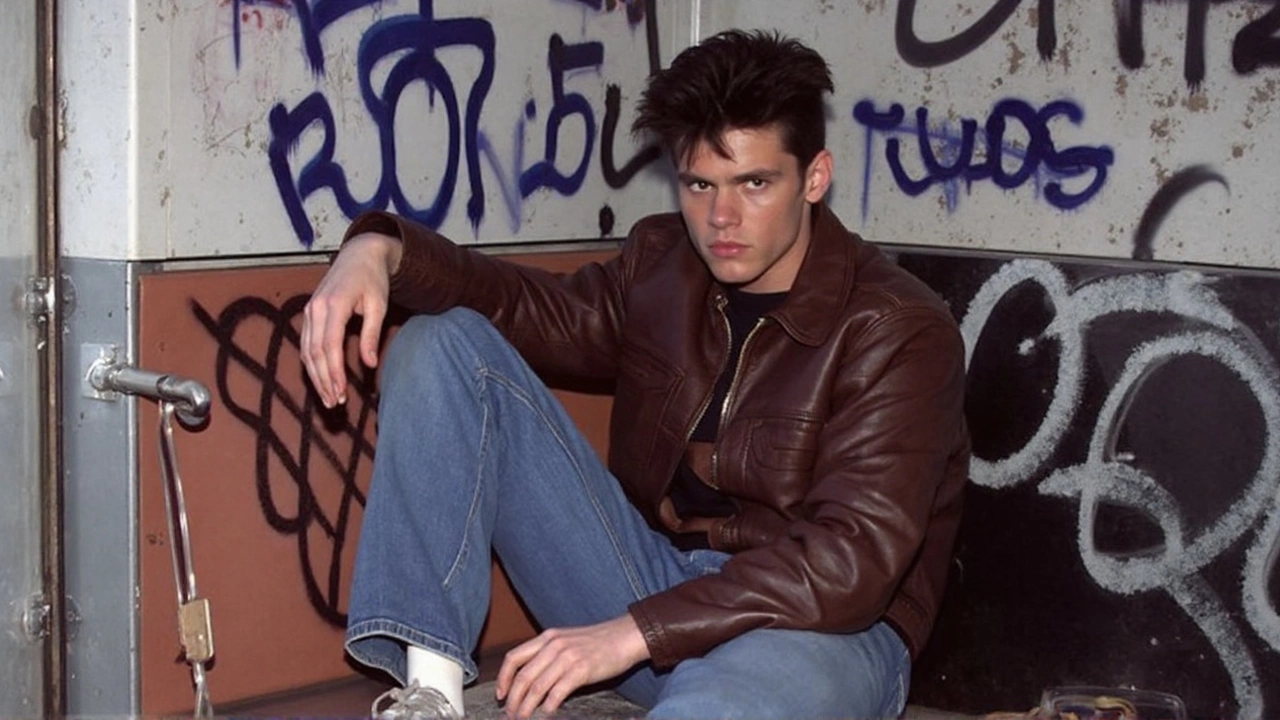

Charlie Sheen says his wild ride through fame and self-destruction is a one-off—something the industry, and the internet, won't let happen again. The 60-year-old actor is laying it all out in a new memoir, The Book of Sheen, and a round of interviews, including a sit-down on Good Morning America with Michael Strahan. He talks bluntly about being "held hostage" by people who had compromising material, paying to keep encounters quiet during his drug years, and why he now sees this moment as a reset, not a comeback.

He doesn't dress it up. In his telling, people from his orbit kept receipts—videos, messages, leverage—and used them. He paid to protect his privacy, especially around sexual encounters he had while using. He describes that period as sampling "the other side of the menu" and says the fear that a stranger could detonate his life at any time was a constant, ugly pressure.

The book, the "reset," and why he's speaking now

The Book of Sheen arrives eight years after he got sober in 2017. He’s been living smaller by design, a sharp contrast to the period when he was the highest-paid actor on TV, pulling in roughly $1.8 million per episode on Two and a Half Men. He told his brother Emilio Estevez in a conversation for Interview Magazine that this isn't about reclaiming a throne. He called it a "reset," and even joked about coming back with a couple of upgrades.

The timing is not subtle. A two-part Netflix documentary about his life is rolling out, promising to retrace the path from Hollywood royalty—son of Martin Sheen, breakout roles in Platoon and Wall Street—to network kingpin and then the most famous meltdown of the internet's early social-media era. He knows what's coming and is choosing to frame it in his own words first.

What sets this book apart from a standard celebrity mea culpa is how direct he is about the mechanics of shame and control. He talks about the economics of silence—who gets paid, how fear spreads, the way private behavior becomes currency once a person is valuable enough to be leveraged. It's not just lurid detail; it's a window into an industry where NDAs, screenshots, and opportunistic middlemen can shape a star's life as much as a studio contract.

He also writes about something more intimate: a speech impediment he masked with alcohol for years. Certain words and sounds were hard to say cleanly, and booze took the edge off enough to bluff his way through. That changed in 2000 on the set of ABC's Spin City. Faced with dialogue he couldn't fake, he finally asked for help. Therapy and coaching gave him tools that a flask never could.

That thread matters because it challenges the "party animal" caricature. For a long time, drinking wasn’t just recreation—it was performance armor. When he set the bottle down for good in 2017, he didn't just stop using; he had to rebuild the parts of himself he had numbed to get through the work.

Why he thinks his saga can’t happen again

When Sheen says his story is unrepeatable, he's not saying no one will crash. He's saying the conditions that launched, fed, and monetized his implosion were oddly specific. In early 2011, he had the biggest sitcom in America, a public feud with his bosses, a live mic, and a new toy called Twitter. "Tiger blood" and "winning" became catchphrases because he was able to broadcast his breakdown in real time, with the tabloid press and cable news strapped to the rollercoaster.

Today's environment is different. Studios and streamers run tighter crisis playbooks. PR and legal teams move faster and earlier. Social media platforms punish messy live drama in ways they didn’t a decade ago, and stars rarely have one giant network show anchoring their fame—it's spread across streaming and franchises. The system is better at cutting oxygen before a brushfire becomes a firestorm.

There's also much less daylight between private and public life. Smartphones are everywhere, cloud backups are permanent, and reputations live or die at algorithm speed. That accelerates scandals, but it also shortens them and splits attention. Sheen's meltdown dominated the culture; today, a comparable story would be one spectacle among dozens in a week, then gone.

Still, the memoir makes clear he isn't dodging blame. He writes as someone who burned bridges, hurt people, and lost the biggest job in television before clawing back a quieter, steadier life. After Two and a Half Men, he headlined Anger Management, which did solid cable numbers but couldn't recreate his network heights. In 2015, he publicly disclosed he is HIV-positive, another moment where he took control of a narrative that others were exploiting.

What sticks is the contrast. On one side: a young movie star in Oliver Stone hits, the slick antihero of Wall Street, the comic bullseye of Hot Shots!, the clubhouse leader of Major League. On the other: a 2011 media frenzy so intense that his name became shorthand for self-immolation. He is now trying to stitch those versions of himself into one story that isn't just a punchline.

His account of blackmail lands like a warning to anyone who still thinks fame and privacy can coexist on old terms. The "quiet payment" era never really ended; it just moved to encrypted chats and hard drives. Sheen's not the first star to talk about paying to make a problem go away. He might be one of the few to walk the audience through what that feels like day after day—sleeping with the knowledge that a stranger could press send.

There’s also a practical read on why he’s speaking now. Memoirs don't just settle old business; they reclaim IP. The Book of Sheen puts his version on the record before the Netflix series, future podcasts, and memoir-adjacent doc projects do it for him. The framing—"reset"—tells readers he’s done chasing headlines and is instead trying to control the terms of his legacy.

He hints at what that looks like in day-to-day life: a smaller circle, fewer nights out, and work chosen for fit rather than splash. The tone isn't sentimental. It's closer to a contractor describing a renovation—take out this wall, reinforce that beam, stop the leaks.

If you're looking for shock value, there’s plenty. But the parts that linger are the craft notes: how he prepared lines when his tongue wouldn’t cooperate, how sober mornings changed his timing, how humility shows up on set. Fans may come for the train wreck; they might stay for the shop talk.

The Netflix documentary will pull the camera back. Expect the familiar greatest hits: Platoon, Wall Street, the sitcom juggernaut, the public firing, the catchphrases that ate the culture. Expect, too, the quieter beats the book foregrounds—speech therapy, relapse triggers, the slow work of staying boring enough to stay healthy.

Calling something unrepeatable in Hollywood is risky. The place runs on remakes. But Sheen’s point is less about him as a singular talent and more about the strange weather system that built around him at a very specific moment. You needed an old-school network star, a new-school viral machine, and a star willing to pour gasoline on both. That mix is hard to bottle.

So he has written the story he wanted to read: messy but unsentimental, clear about the cost, stubborn about the possibility of change. Not a comeback. A reset. And, if he’s right, the last of its kind.